DRESDEN: DESTRUCTION, RENEWAL AND POST-WAR RECONCILIATION, January 2020

A talk by Marcus Ferrar, Chairman, The Dresden Trust

A MORAL ISSUE

On 13th and 14th February 1945, the British Royal Air Force destroyed the historical centre of Dresden, considered one of the most magnificent cultural jewels of Europe. It was one of the most devastating attacks by bombers which had developed fearsome powers to strike at the heart of Germany as World War II came to a climax. Yet as soon as it was finished, the British began to feel a bad conscience. Was it morally right? And if not, what should the British do about it? The Dresden Trust offers an example of successful reconciliation.

THE RAID

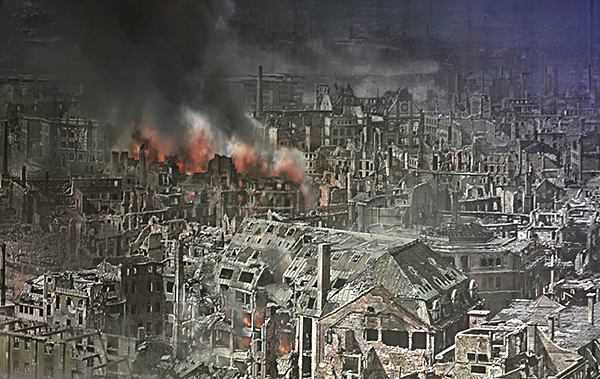

Attacking in two waves in the evening of the 13th and the early hours of the 14th, 800 British bombers dropped 2,700 tons of high explosives to blow open buildings, and then 200,000 incendiaries to set the wreckage on fire and create a firestorm. Some 20,000 people were killed, many of them suffocated for lack of oxygen and then burnt to cinders. Crews of the second wave of bombers could see their fiery target 500 miles away. As the commander of the raid circled over the city to direct them in, he radioed: “It’s coming up quite nicely now.”

78,000 dwellings were completely destroyed, and tens of thousands rendered uninhabitable. Famous buildings such as the Zwinger art gallery and the Semper Opera house lay in ruins, and the baroque Frauenkirche (Church of Our Lady) collapsed into a heap of charred rubble. The city burned for seven days, and 30 years later flat spaces, weeds and grass still stretched as far as the eye could see. Sheep were set to graze around the stones of the Frauenkirche.

The British deliberately targeted the historic centre, since the old wooden-framed houses could be readily blown apart to create the firestorm. It was a technique they had mastered since 1943. Dresden had military-industrial workshops and railway marshalling yards too, but they were scattered around the periphery and hard to target. Follow-up attacks on these targets by the U.S. Air Force on 14th and 15th February did only scattered damage. Most of the casualties were therefore civilians.

THE PROS

The British saw some justification in such terrible tactics. The war was by no means finished. German armies continued to fight fiercely all over Europe, and German rockets were demoralising the population of London. Too weak to launch land attacks in Europe for most of the war, the British could hit back effectively at Germany only by aerial bombing. Daytime bombing allowed accurate targeting of military objects, but the attackers could be too easily shot down. Night-time gave better cover, but bombs were bound to fall also on civilian housing near the targets. Many British saw no cause for regret for this: if German civilians suffered, they had only themselves to blame for supporting Hitler in his war of aggression. Moreover the Germans were first to bomb civilians – in Warsaw, Rotterdam, Minsk, London and Coventry. Overall, Britons felt there were strong arguments for taking deadly revenge – even if it involved incinerating tens of thousands of civilians.

THE CONS

Deliberate bombing of civilians violates international treaties to which Britain is committed. The attack on Dresden would thus today be considered a war crime. In 1945 this was less clear: the relevant Hague Convention then forbade bombing of undefended civilian targets. Dresden was defended, but only very lightly.

Whether or not it broke international law, many British consider the attack on Dresden inhuman and thus morally wrong. The British should not descend to the levels of cruelty of others.

It was also argued that Britain should not destroy great cultural treasures – which the historic centre of Dresden undoubtedly was.

Another objection was that carpet bombing of German cities constituted terror warfare: the Royal Air Force strategy was to destroy German morale, and thus end the war quickly. British authorities were untruthful in insisting they were only targeting military targets.

Finally, bombing of German civilian centres failed to achieve its goal. Albeit under some duress, German civilians continued to support the Nazi regime, and the war went on to May 1945, considerably longer than expected. In hindsight, diverting attacking resources from cities to enemy military forces, industry, oil supplies and railways could have ended the war earlier.

BRITISH REACTION

There were adverse reactions immediately afterwards. A British officer briefing foreign correspondents let slip that one aim was to damage German morale. An American Associated Press correspondent picked on this to report that “Allied air chiefs have made the long awaited decision to adopt deliberate terror-bombing of German population centers as a ruthless expedient of hastening Hitler’s doom.” The assertion that only military objects were targeted no longer held water.

Winston Churchill drafted a memo reading “I feel the need for more precise concentration upon military objectives …rather than on mere acts of terror and wanton destruction, however impressive.” After his air force chiefs pointed that he himself had authorised the raid, he withdrew the draft. The version circulated did not mention “acts of terror and wanton destruction”, but urged focus on military objectives so that Britain would not have to take over a ruined land.

After Dresden, the Royal Air Force fire-bombed Pforzheim, a centre of jewellery and watchmaking, killing 17,000 of the 53,000 population. However after the war ended, the commander of Bomber Command, Arthur Harris, was cold-shouldered and only after 2000 was a low-key memorial to bomber pilots put up in London. The British continued to have a bad conscience over the bombing of German cities, and the main focus was Dresden.

RECONCILIATION BLOCKED IN COMMUNIST YEARS

From 1945 until 1989, Dresden was isolated inside Communist East Germany. The regime declared that the British destruction was a “terror attack” and a “war crime.” Some in the UK agreed with this, but the Communist judgement was motivated primarily by ideology. The Nazis were a product of the bourgeoisie, and as the British were “bourgeois” too, they were the ideological enemy and deserved no credit for defeating the Nazis. There was no unanimity.

Communist authorities restored the Zwinger art gallery and the Semper Opera House and gradually rebuilt other parts of the city centre, but left the Frauenkirche as a heap of ruins. Nearby they erected a huge concrete Palace of Culture. The moral: religion is dead and the future is secular.

Under these unfavourable circumstances, moves for reconciliation between Britain and Dresden were limited to small-scale initiatives by the people of Coventry.

FALL OF THE BERLIN WALL – WAY OPENS FOR RECONCILIATION

After the East German Communist regime collapsed and Germany re-united in 1990, the way cleared for the British to make amends for 1945. United Germany adopted democracy and its leaders acknowledged collective German responsibility for World War II. There was a meeting of minds between Germany and Britain.

But the auspices were still not favourable. In 1992, the British belatedly put up a statue in London to Arthur “Bomber” Harris, who had organised the bombing of Dresden. This went down badly with Dresdners. When HM Queen Elizabeth II paid a visit in that year, she received a chilly reception and an egg was thrown at her.

At this point, Dr Alan Russell, a former European civil servant, decided he and his British compatriots needed to act. For the first time in his life he demonstrated with a protest placard at the unveiling of the memorial to “Bomber” Harris. In response to a “Call from Dresden” asking the world to help rebuild the Frauenkirche, he founded The Dresden Trust in 1993. Over the next 10 years, he rallied British society around the Trust’s campaign to raise funds, which eventually exceeded £1 million. The Trust commissioned a golden orb and cross from a London goldsmith, Grant Macdonald. In 2005, this was hoisted to the top of the cupola of the rebuilt church in the presence of thousands of Dresdners and HRH The Duke of Kent, who for over 25 years has been the Trust’s Royal Patron. The Queen hosted fund-raising dinners and contributed from her own pocket, as did the British Government.

Not all Britons wished to apologise or say sorry. They spoke instead of “healing the wounds of war” and “never again”. However the experience of The Dresden Trust shows that deeds are more important than words. Britons were ready to rally around a campaign to rebuild one of Europe’s most beautiful churches and top it with a golden orb and cross “made in Britain”. Without necessarily having to speak out, they could assuage an uneasy conscience with a substantial gesture of atonement. It worked. The hostile mood in Dresden dissipated, and since then Britons have been warmly welcomed there.

THE DRESDEN TRUST IN THE FUTURE

The Dresden Trust did not want this to be an isolated action: it believed that once bridges have been built they should be walked over. It therefore resolved to undertake further initiatives in Dresden so that reconciliation evolves into lasting friendship. In 2018, it was lead sponsor of a new space of green trees and benches across the Neumarkt square from the Frauenkirche. It also extended the scope of its longstanding Dresden Scholars Scheme of school exchanges.

Marcus Ferrar, January 2020, www.dresdentrust.org